By Ryan L. Farmer, Oklahoma State University

Assembling a curriculum vitae (CV) can simultaneously be exciting and daunting. Okay, maybe exciting is an exaggeration. But some folks—myself included—really enjoy updating their CV. Why? Well, it’s an opportunity to reflect, to think about what I have accomplished, and to compare what I have done with what I would like to do. In this way, I use my CV as a self-evaluation of my progress.

Whether you want to use your CV in this way or not, there’s no denying that the CV is used as an evaluation tool by others. Whether you’re applying for an internship, a postdoctoral fellowship, an academic position, a clinical position, or going up for promotion or tenure, the CV plays an integral role in documenting your professional identity and activities. In fact, the CV is one of the first documents that hiring, search, and tenure and promotion committees will look at. Just because the CV is used as an evaluation tool doesn’t mean it doesn’t serve other purposes; you can use your CV to inform and persuade others. It can also serve as a reflection of who you are as a professional. A well-formatted, informational CV can go a long way. In comparison, a sloppy or uninformative CV can make a committee’s job harder, which can mean losing the position or not getting a promotion.

So why are we here? The goal is to talk about some standard CV guidelines (not rules), to talk about different ways to document your professional activities, and to share some ideas and templates. First off, a CV is different from your more traditional resume in that it’s longer and more comprehensive. Some would say, there are no length or space restrictions. Secondly, the traditional CV isn’t the only game in town (though it is by far the most common). There are two general types of CV: The traditional CV and the narrative CV, which was developed by the Royal Society & UK Reproducibility Network. The primary distinction between these formats is the former encourages listing activities and products with brief descriptions while the narrative format uses a series of prompts to evoke a narrative response about one’s professional activities and products. The purpose of the narrative format was to de-emphasize the notion of performance indicators (e.g., publication count) and to build a more comprehensive narrative of a person’s professional work. While this is a noble goal, it has not been readily adopted by many programs at this time and so our focus will be on the traditional CV in this blog post.

General Advice

When developing your CV, remember that your ultimate goal is to communicate your professional activities and details to someone who may not be familiar with you or your work. As a result, being straightforward, well-organized, and focused will help you in achieving your goals. Additionally, while the CV is pretty structured, you should focus on you and your goals. Both the content and the order of the content are flexible, and so you should design your CV to highlight aspects of your professional work that are relevant to the situation. Treat it as a dynamic document that can be reorganized for particular uses. If you’re applying for a research position, you might lead with publications, presentations, and grants. In contrast, if you’re applying for a clinical position, you may want to highlight your clinical license(s) as well as your past clinical positions and field-based or applied experiences. Finally, those applying for predominately teaching positions may want to highlight their past teaching experiences and the courses they’ve taught in the beginning while moving research activities and publications to the end. There is no right or wrong way to build your CV–just make sure it fits your purposes.

Also remember that your CV is an evolving document, and so frequently updating the content is crucial to communicating accurately. While it may be feasible to update after a long period of time, you may find it more difficult to recall details. What was the name of that committee? What presentations did I do, again? Many folks update monthly, though, for major products (e.g., a publication), I strongly encourage dropping the details in as soon as you have them. For me, I am sure to forget something I’ve done—a local presentation, an open-source document or figure, or a science communication effort—if I try and do it in batches later on.

Before I jump to some basics, I wanted to provide a few wonderful links. Dr. Sara Hart provided this wonderful PowerPoint on CV basics. Some other folks offered their insights, examples, and a bit of humor that folks may find useful.

Let’s talk CV construction what tips have you got? #AcademicChatter #AcademicTwitter #phdchat @OpenAcademics #schoolpsychology and #behaviortwitter. How’re you documenting outreach, #scicomm, and other unique experiences? I want it all!

— Ryan 🧑🌾 (@rfarmer27) March 21, 2021

Outreach: pic.twitter.com/EqMFnkd96W

— S. Mason Garrison, PhD🌈🤹🏻♀️💫🧬 (@SMasonGarrison) March 22, 2021

There are very few 'musts' in C.V. construction. But our family rule is, *always* have someone else read it before you send it off. Preferably someone critical and/or curious, who will ask questions & point things out.

If you've read this and don't have someone in mind? Ask me.— Alex Dresner is vaccinated, but wearing a mask (@madDoctorAlex) March 22, 2021

When writing a CV, it’s crucial that it appears clean and polished at the end. One way to do that is to ensure that your formatting is thought out and consistent throughout the document. Pick a font (at max, two) and use them strategically. All of your text at a given level (e.g., body) should be in the same font and at the same size. It’s okay to vary up your headers a bit (different font or font size) to help others navigate your document. But for the love of all that is good in this universe, don’t treat this as an abstract art exhibit. While it’s the content that matters, how we present that content may bias reviewers.

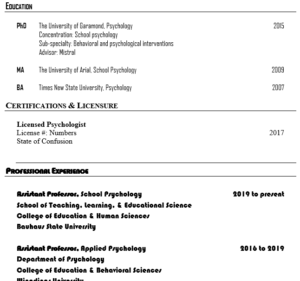

Screen capture of a CV that uses three different fonts across three sections. The third font is illegible.

Another good thing to consider here is the readability of fonts. While it’s not wise to vary up the fonts across your document, at least the fonts in the first two sections (Education and Certification & Licensure) are easily read. Fonts.com argues it’s “all about legibility” in design, and I argue that this is true for CVs as well! Keep it clean and make it easy for others to read. Fonts.com provides wonderful information about selecting fonts. Like Fonts.com, Adobe Fonts lets you search and filter by type of font. However, there’s still a lot of options and it may not always be evident which ones will translate well to print or a pdf document. These excellent blog post from The Paper Mill Store and Practical Typography discuss many of these issues and offers suggestions for fonts. You won’t be surprised to learn that Times New Roman is amongst those suggested. If you’re not feeling adventurous, no one will judge you for sticking with the classic. In general, you want to avoid stylized, cursive, and impact fonts as those tend to be harder to read.

Another CV basic is the margins of your document. Arguably, this is a preference to some extent. Those who want to read more can do so here at Practical Typography. That said, I’m a big believer in not trying to fix something that isn’t broken. The defaults in your word processor are fine. That said, you want to keep it consistent throughout your document. The last big decisions you’ll have to make are how to use spacing, tabs, tables, and horizontal rules to organize your document. There are wonderful resources for learning about the details at Practical Typography, but you may want to look at examples from others in the field and see how they’ve managed these elements. Find something you like or mostly like and tweak it. The best advice I can give here is to keep it consistent throughout your document; this may require slightly more planning upfront, but it’s worth it in the end. Okay, enough of the nitty-gritty. Let’s talk content!

The Content

For the most part, there are a number of standard sections and you can find a plethora of ways to organize and format these sections online. Note that some universities or committees may request specific breakdowns, such as the Boyer categories or institution-specific (e.g., Scholarship, Service, Outreach) categories. As such, the following should be taken as general advice, and readers should check with their institutions to see if there are specific requirements.

- Education

- Clinical experiences (e.g., practica, clinical positions)

- Professional experience (e.g., professional, non-clinical positions)

- Teaching experience (e.g., courses taught, teaching positions)

- Publications with subsections

- Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

- Book Chapters

- Reviews (e.g., test reviews)

- Presentations with subsections

- National

- International

- Regional

- Local & University Presentations

- Funding

- Certifications & Licensure

- Honors & Awards

- Membership and Professional Affiliations

- Service with subsections

- National (e.g., NASP, editorial boards)

- State & Regional (e.g., state associations)

- Local & University (e.g., committees, organizations)

- You may need to break this down further to document service at the department, college, and university levels, depending on the expectations of your promotion committee.

Since we don’t want to reinvent the wheel, we’ll only cover these briefly with a few pieces of general advice. For instance, what if you don’t have content to go under each section? Some good advice I’ve gotten is to simply exclude a section or to combine sections. For instance, early career researchers may not have a ton of publications, and so dividing them out in subsections may look a little odd. So long as you’re candid about your content (e.g., specifying that a publication is a chapter versus a peer-reviewed publication), this shouldn’t be a problem. Another piece of general advice here is to add totals at the top of each section (and maybe subsection). Yes, we know that counting publications is a pretty poor way of accounting for a person’s contributions (e.g., Büttner et al., 2020), but unfortunately many of the committees we’re submitting CVs to still operate under this paradigm, so let’s make the process clearer when we can.

While how you document this information is a bit of a personal preference, there are a few standards you should be aware of. For instance, reverse chronological order (i.e., newest at the top) should be used whenever possible to highlight what you’ve been doing most recently. Whenever possible, use APA style to format information. While APA doesn’t offer styles for everything (e.g., funding) you might want to include, they offer a great deal of information about how to document publications, presentations, podcasts, and so forth that may be useful.

A lot of the standard approaches to building a CV have been around for a good long while, and that may make it difficult to figure out how to include other types of content. For instance, it’s surprisingly hard to find a good, authoritative source on how to document awards and funding. One great source is Walden University’s section on documenting grants. For instance, they recommend this general format:

- Current Research

- Grant # (PI Name)

- Name of Funding Organization (no acronyms)

- Amount of Award

- Period of Grant Award

- Title of Project

- Role on Project (if not PI)

Certainly, the key elements are there and it may be worth documenting your funded (and unfunded) projects in this way, especially if you want them to stand out in your CV. A more streamlined approach, however, might be to approximate an APA format for the funded project. Something like this.

- Name of Funding Organization (no acronyms). Amount of Award, Period of Award. Title of Project & Grant # (if applicable). PI Name. Role on Project (if not PI).

Documenting Non-Traditional Contributions

There don’t seem to be any hard and fast rules here, so find a format that works for you and—you guessed it—be consistent. Similarly, there’s little guidance out there on how to document more contemporary contributions to science and practice, such as the creation of software, leading national book or journal clubs, engaging in science communication, and so forth. One option is simply to create subcategories, or a new section, called Public Scholarship to capture some of these activities. This can be a bit imprecise as some are more like traditional scholarship (e.g., an open data set) while others are not (e.g., science communication). I have taken the route of creating a Public Scholarship section and specifying that it is not peer reviewed. Under that, I list subsections for podcasts, science communication and white papers, and blog posts (like this one!). That said, I’m not claiming my approach is right. Some authors have started thinking and working on these issues. Recently, Acquaviva et al (2020) helped to define the notion of Social Media Engagement as an aspect of Public Scholarship both in terms of including social media outreach and activities in the promotion and tenure process, but also in offering guidelines for how such content might be documented. For instance, documenting engagement in social media overall is relatively straightforward, and may look something like this:

- Twitter: @rfarmer27. 2019 to present

- 897 followers. 37,100 impressions.

- 87 tweets.

or

- Facebook: EBSPsych. 2018 to 2020

- 7,382 followers. 27,000 user reach.

- https://www.facebook.com/EBSPsych/notifications

Acquaviva et al. (2020) offer more specific guidance for individual social media efforts, but I don’t wish to repeat them here. I strongly encourage folks to check out their work for more details.

In addition to how we document public scholarship, I want to talk a little about how we might verify these contributions. For instance, when creating and uploading digital presentations, podcasts, or static images (e.g., infographics), users might consider Figshare or Open Science Framework (OSF). Figshare may be ideal for individual files or presentations whereas OSF more appropriate for projects that consist of several files. The benefit of these services over personal repositories is the ability to generate digital object identifiers and static links. An alternative for video recordings is YouTube, which also provides a permanent link. In addition to details for describing and accessing the content, scholars may want to provide metrics for these materials, such as the number of participants, the reach, and so forth.

This said, these guidelines are very much in their infancy and there are a number of ways to document these types of activities. For instance, Dr. Garrison offered a few screen-captures from her CV demonstrating how she documents her contributions to online forums, software packages, and even skills!

I include a ton of bonus stuff, r packages, social media, and my department has been wonderfully supportive in counting it. (Primarily as service and outreach.) https://t.co/1D21gr09Lv highlights 🧵⬇

— S. Mason Garrison, PhD🌈🤹🏻♀️💫🧬 (@SMasonGarrison) March 22, 2021

Documenting Transparency & Open Science Efforts

Additionally, we might go about documenting various transparency efforts on our CV as an indication of our contributions and as indicators of scientific rigor. Some of you may be familiar with open science badges. It’s relatively straightforward to include these badges and relevant links right into your CV to highlight your transparency efforts. Consider this example from my CV.

We’ve documented that we have open stimulus materials (in this case, a survey) and a hyperlink to the OSF project where those details can be found. It would be relatively little effort to modify this to specify that we’ve posted open data, open code, or that we pre-registered the project. We didn’t, so we don’t have those elements here. These badges are available with attribution to the OSF and can highlight these efforts. It might be virtue signaling, but it’s also an indication that you value transparency in your work, and it just might be viewed fondly by your committee!

Conclusion

Frankly, there’s so much content here that it was hard to select what to include. I tried to be responsive to questions we received following our blog post on science communication, to address common concerns, and to provide a plethora of resources. Toward that last point, we’ve assembled an OSF project on CV construction. If folks want to contribute by adding resources, examples, or templates, please contact Ryan Farmer at r.farmer@okstate.edu or request access as a contributor via the OSF project page.

What other recommendations do you have for making the most of CV prep? What tips or tricks make the process less arduous? Let us know what we missed and how we might expand on these and related topics!